EB: You cover some timely and pressing matters that the art world is tackling today. What role does bias and objectivity play in your work?

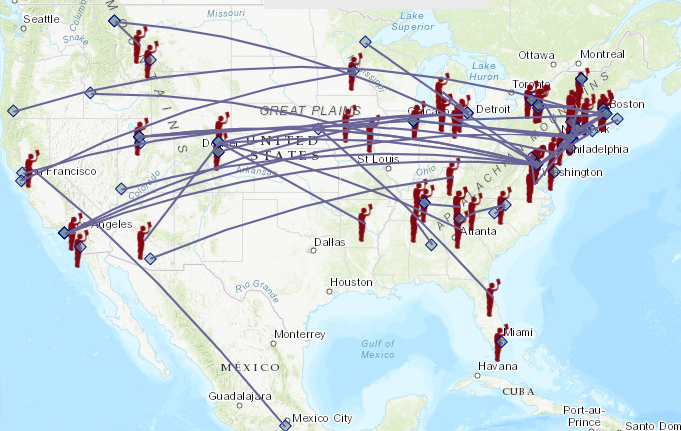

DSG: There is no such thing as objective art history, though some digital art historians might disagree with me. But what you can do is think really carefully about your research question and if your data set is limiting your ability to answer that research question. For example, if we want to study the role of women artists in nineteenth-century France, and all we used was the collection at the Musée d’Orsay, the research would be very limited. If you were to expand your data set to include the names of artists everyone displayed at the Paris Salon, the data gets broader, but not complete. And then you could even go further to other shows that are happening outside of Paris.

There will always be bias in the data you choose. You can mitigate some of the bias by casting a wider net. And one of the ways you can recapture a wider net is by using giant spreadsheets. Cognitively, you can’t do a study of 120,000 paintings by looking at each one individually, but it becomes possible when you engage with a digital method. My ongoing joke is that my dissertation should be titled “Painting in Spreadsheets.” Sometimes fancy digital stuff can make things seem overcomplicated. You can learn so much from a graph generated in Excel.

EB: You are currently the Digital Art History Editor at Panorama. What is your role within Panorama’s initiative, Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History?

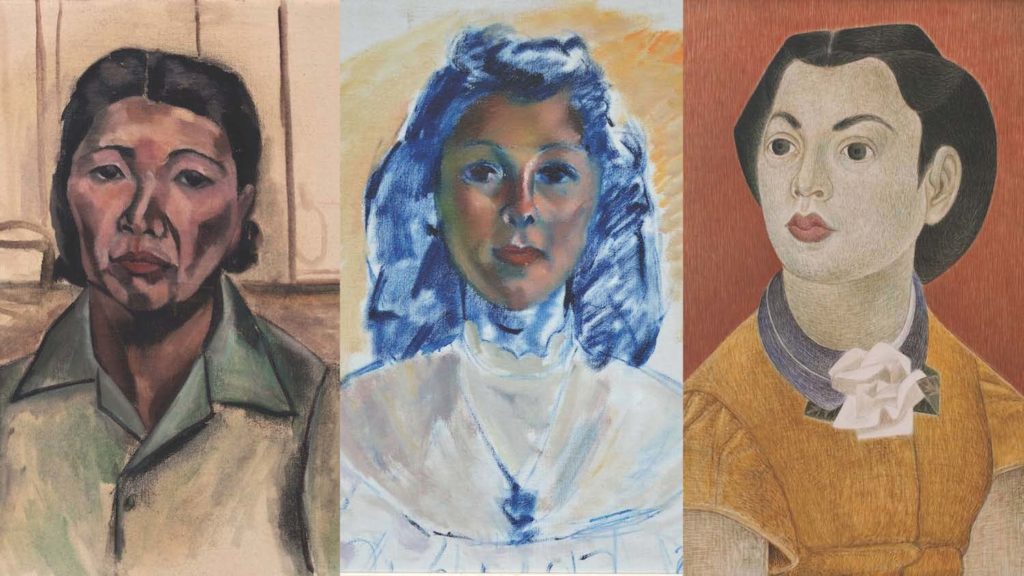

DSG: I came to this initiative after it was preconceived by John Bowles [University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill], who did a great job thinking about what it means to be a more inclusive digital art history. We defined it in a series of ways. First, who has access to technology and resources or, for example, a digital humanities lab. Then, it’s about knowing where to start when you begin a digital project. Third, it’s about using digital art history to tell stories that are otherwise invisible or haven’t been included in the story of American art.

Over the course of months with the five workshop participants, we engaged with them to help them figure out how to analyze their data sets, classify information, structure an analysis, know what analysis software exists, and even piece together what makes a good digital art history question.

EB: It sounds like you are focusing on building competency among scholars. How did this work within the structure of the workshop of Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History?

DSG: For Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History, the workshops and events were virtual. In a way, I think that made the program even more accessible. It wasn’t a one- or two-shot workshop. We were able to keep momentum and stay engaged with our participants.

Before the first workshop, Johnathan Hardy, who is currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Minnesota, and I had discussions with each participant after looking at their data and their hypotheses, and we helped them include visualizations. At the first workshop, they presented their projects to each other. Then there were a series of back-and-forths where they showed us demographics, and Johnathan would help them tweak things. We also gave basic talks about statistics for historians, for example, or how to tell a story with pictures. The participants continued to work, and we followed up with them to keep thinking about what else is possible.

EB: What would you say are the largest roadblocks in the field that you were able to overcome with Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History, and what is this initiative’s legacy?

DSG: Because it is a finite initiative for the participants, we emphasized independence in learning how to do this research themselves. It’s a heavy lift to teach someone how to do this. Access to resources is also a roadblock because there is a lot of hesitancy and fear among art historians who don’t have any sort of statistical or quantitative training. The first step of even having someone talk you through this kind of work isn’t available at many universities.

The other risk is that you can do a summer institute, or you can take a class to learn these methods, but if you’re not applying it to a project now, those skills can get rusty quickly.

We would not have had the capacity to solicit this type of work nor the ability to support it and build momentum in American art without the grant support, and it’s already paying off. I had a meeting with some colleagues at Williams [College] about analyzing the metadata related to how nationalities are recorded in museums’ online collections. They said they should send any future article about this topic to Panorama. This is because they’ve seen Panorama, as an important journal in the field, give a platform to digital art history research. Panorama has made it clear that American art history is open to and supports different approaches. This is of huge value to the field.