KB: Can you describe the chronologic and geographic scope of the exhibition and its impact on the traditional canon of abstraction?

CM: The exhibition begins in 1862 in England with the first watercolors and gouaches on paper by Georgiana Houghton, works that were rediscovered a few years ago. These works demonstrate how an abstraction linked to spiritualism appeared much earlier than previously believed. It is still a representational abstraction, linked to the transcendental. The exhibition ends in China with the works of Irene Chou from the 1990s, which combine the tradition of ink painting, Taoism, and Abstract Expressionism. The spectrum is therefore very open, both chronologically and geographically, which in effect broadens the aesthetic canons of abstraction.

KB: In what ways does this exhibition disrupt the history of abstraction?

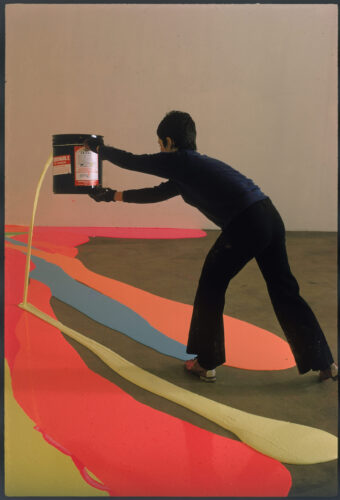

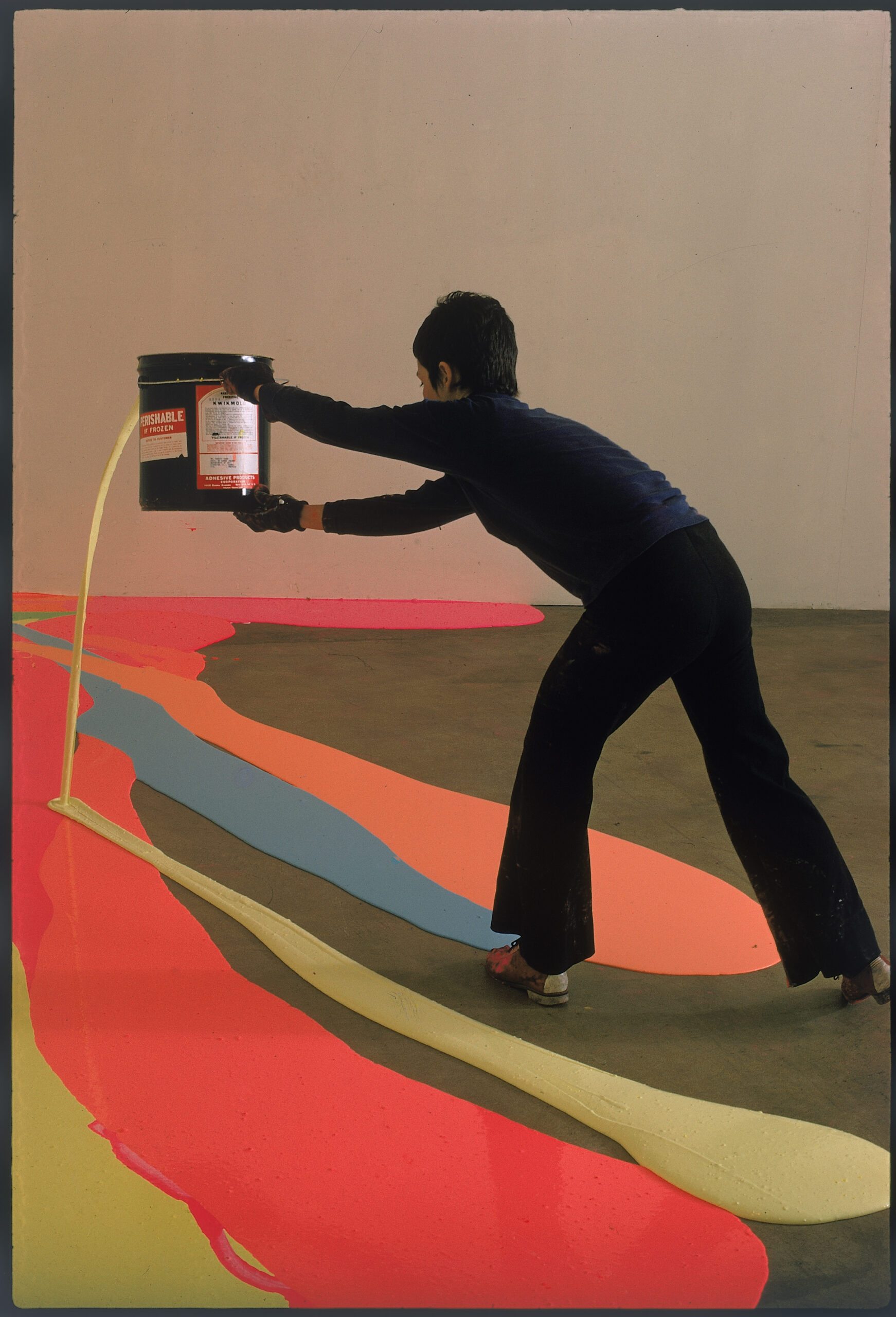

CM: I could speak of an extended approach to abstraction as a plastic language or “expanded abstraction.” First of all, it means looking beyond painting, to think about how this abstract language can bring about dialogue between the so-called major and minor arts, removing the hierarchy of practices, in particular in relation to the so-called decorative arts. I also include dance and performative abstraction, which began as early as the end of the nineteenth century with the serpentine dance of Loie Fuller, as well as photography and film.

CM: I look at the “impure” influences of abstraction, moving away from the canons established by Alfred Barr in 1936 with the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art at the Museum of Modern Art or by the group Abstraction-Création in France. The exhibition considers abstraction linked with theosophy—abstraction thought of as a geometrization of the body, abstraction linked to textile practices and everyday arts, etc.

KB: Why do you think it is important or necessary to dedicate a major exhibition to women artists in 2021?

CM: I would clarify that the exhibition is devoted to women artists who have been rendered more or less invisible in the history of abstraction (which does not mean they are invisible), or whose unique contribution has not been sufficiently explained. It is not simply an exhibition on women artists but a reinterpretation of the history of abstraction, which puts these artists in their proper place with their distinctive features and originality.