EMG: Why is it important to track the footpath of the US military and its impact on the environment?

MDB: One of the exhibition’s goals is to bring public awareness to the impact of military research, testing, training and resource extraction on the domestic landscape. If we are going to understand our current environmental and public health challenges, we need to know the origin. There have been exhibitions about the impact of nuclear weapons proliferation on the environment, but this expands the discussion to military activity more broadly. From an artistic perspective, artists consider questions like, what does it mean to make a photograph of something that is difficult to see and measure? How do you portray something that engages history, and how do contend with things happening on a massive geographic scale? How do we document it? In the process of addressing these kinds of questions, artists challenge old frameworks with new conceptual and rhetorical approaches. I am inspired by the work of these artists to try to portray these issues, by their visual storytelling, and by the collaborations they have with scientists, community groups, and journalists.

EMG: The exhibition highlights 60 artists who range from professional photographic artists and photographic journalists to lesser-known and emerging photographers. Why is it important for Devour the Land to showcase these diverse perspectives?

MDB: People of color have been trying to call attention to and have been protesting impact of militarism for a long time, but these people of color as subjects and as makers have been overlooked and are not as dominant in the field of environmental photography. I also wanted to include women like Dorothy Marder, whose work ends up in the archives, but not necessarily exhibitions. I wanted to bring photobooks to the world of fine art and show a range of photography practices. There isn’t only one idea, but also variety, depth, and people you may not have heard of prior to this exhibition. Part of the scholarly interest of this project is how narratives in the 1970s were dominated by a particular story and photographers, and through this show, we can demonstrate how militarism and racism are also a part of these stories.

EMG: Communities of color and their relationship to land play an integral part in this exhibition. This project highlights these communities that are often overlooked in environmental photography, while bearing the most direct environmental effects of the militarized landscape. What do you hope audiences learn from this knowledge?

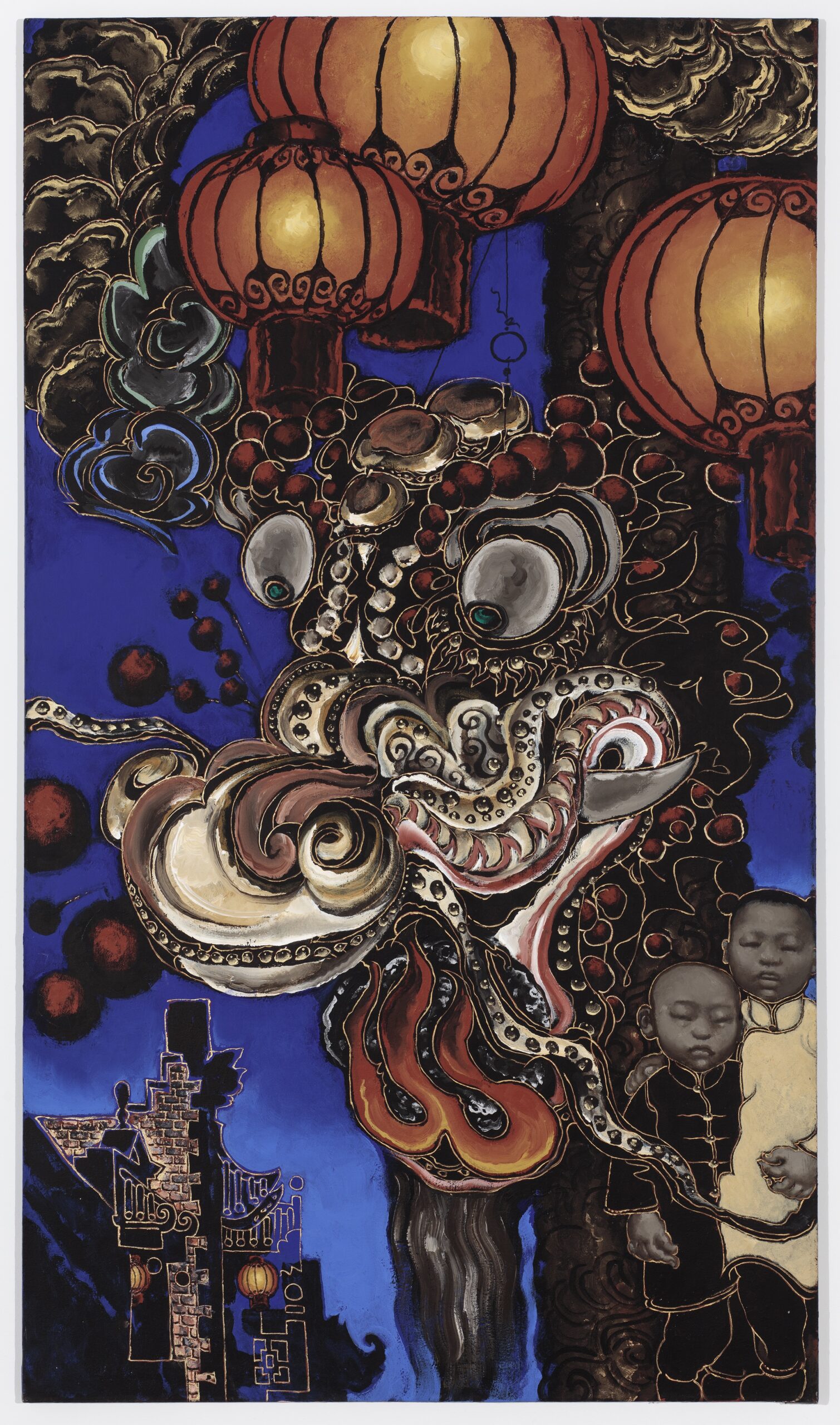

MDB: Photography exhibitions on the environment are often not associated with curators of color. I hope this project helps to shift expectations around who works on what kinds of topics. Communities of color face distinct challenges, and while there has been activism around this issue, this is not included in the story of environmental photography. I wanted to broaden how we think about landscape, especially in urban areas, and to demonstrate that you don’t have to live in rural areas to be a part of the natural world. The impacts of health and economics are very real. We must understand what people live with and what challenges people are living with. If we are going to address the issues of poverty, we must understand what is contributing to the cause. We must think about uneven policies like why areas become dumping areas and why others don’t, as well as why certain voices aren’t heard. My curating is about drawing on my own awareness and what I have been exposed to.

EMG: Photographs by women and the role of photography as a form of activism have a significant connection to each other in the exhibition. These documentarians brought attention to “militarism as intersectional—relating to human rights, the rights of nature, and the fiscal and ethical responsibility of nations.” What information or knowledge stood out to you the most?

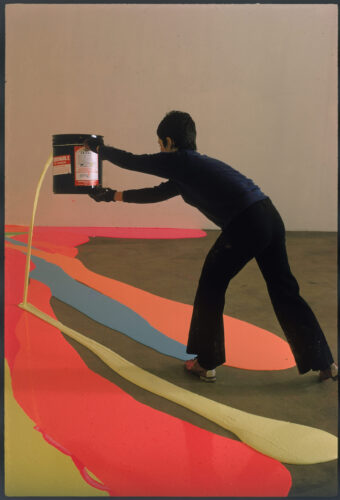

MDB: What stood out to me was how women and people of color know about these issues intimately, because they understand oppression and were thinking about issues of militarism and human rights before others. Women and people of color have always had an activist stance, and what also stood out to me was how some were recording as artistic expression and others are physically expressing themselves, such as people dancing at nuclear stations. I was drawn to the idea of creativity as a weapon. For the photobooks, I saw the way women used humble means and humor or satire to read broader trends around hypocrisy, which was striking to me. The photographs explore the lives of everyday people who become politicized and moved to take action. The exhibition ends with a section called “Resistance,” which is about activism. The photographs spoke to me because they depict the work of people to take on corporations, educate themselves, and ultimately, do what they can. It shows how everyday people bring attention to things that are happening to them and where they live. They are photographs of individuals, but they are about people across the country.

EMG: The catalogue will include a section by photographer Will Wilson on his project to document uranium mining on Navajo land. Why did you include this story in the publication?

MDB: I knew about these stories and their ties to stories about cancer alley. From Native land to land theft of African American farmers, I asked about how the communities’ land was taken and wanted to make a connection between cancer alley and Will Wilson. Those images speak to intergenerational trauma. One idea in the show is that just because you grew up in the city doesn’t mean there’s no connection to the land. Activism is always present, and oppression has tried to take our connection to the land away. I wanted to demonstrate a wider conversation in the arts. Wilson is writing about this as an artist and writer. I wanted to show that as an Indigenous man, he’s a part of this conversation and to promote other perspectives. I also wanted to honor a similarly long history like African American farmers with Indigenous writers on ecology.

EMG: What else do you hope your audiences learn from your exhibition?

MDB: It is a show that asks us to consider the costs of conflict to our environment. When we talk about loss of life and soldiers, what are the other costs to our environment at home and what are the costs on mental health? The show is about peace and the great costs of armed conflict and militarism. One artist said the idea to “Devour the Land” is like the nuclear that will devour the gene pool. We have to think about the costs of all of this, and remediation to clean the costs. We also need to think about how photography expands theses narratives and presents iconic memories. The show starts during the Civil War and presents war’s ongoing legacies.