Author:

Rick Cardis, Evanston Township High School

Summary:

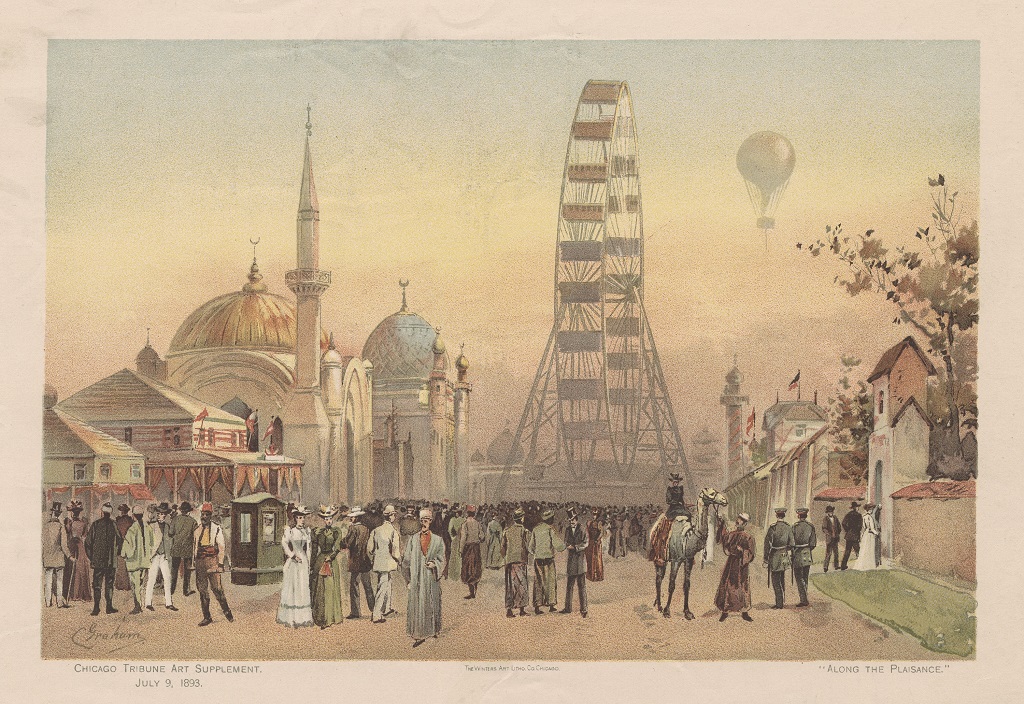

This lesson will deal with the experience of immigrants in Chicago from 1890-1950. Students will analyze artwork and primary sources to compare and contrast the way various texts address the factors that pushed and pulled immigrants and migrants to Chicago and other U.S. cities in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Students will consider why African Americans in the South, Mexicans, and Eastern European Jews left their homes. They will also analyze why Chicago and other U.S. cities were desirable destinations. Students will share their findings in oral presentations and will create a Venn diagram that compares the push and pull factors encountered by these different groups. As a concluding activity, students will write narratives that illustrate the push and pull factors that led migrants and immigrants to Chicago.

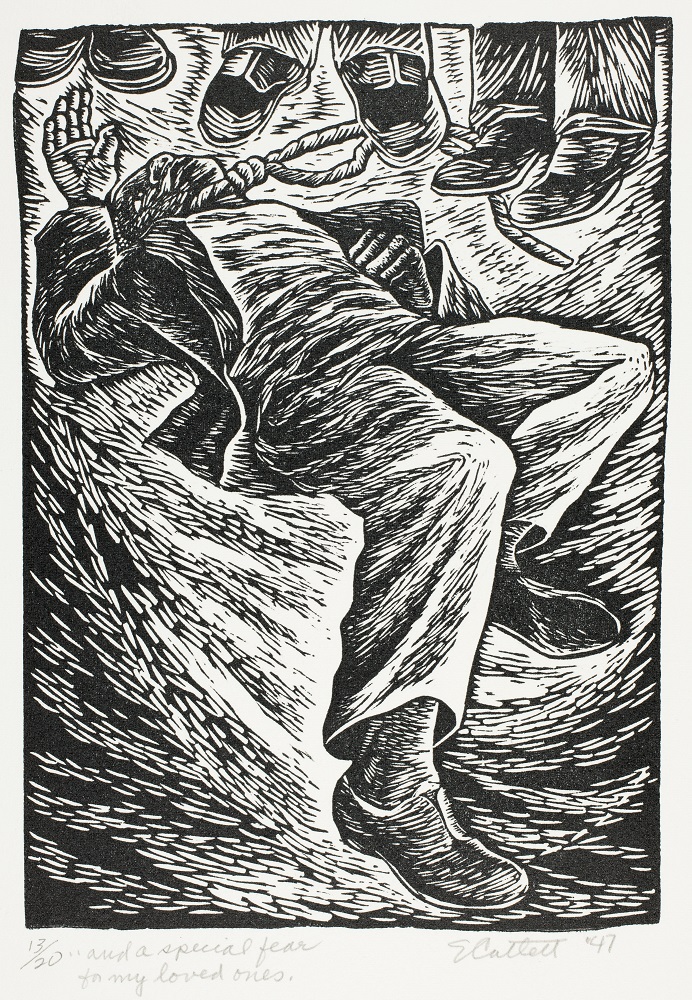

Please note: Some of the primary sources for this lesson use racially offensive language and describe violent acts motivated by racism and prejudice. One of the artworks used in this lesson depicts the aftermath of a lynching. Review the materials ahead of time so you know what to expect. Prepare students by discussing why it is important to examine these sources even though they are troubling. You may wish to describe their historical and social context and explain that the goal of this lesson is to examine the hardships that pushed people to leave their homes, which included experiences of racism and violent persecution.

Lesson Overview

Grade Levels: 9–11

Time Needed: 5 class periods, 40–50 minutes each

Background Needed

The following lesson may be a useful preparation for this lesson, since it will introduce the topic of the Great Migration and will help students learn to closely analyze a work of art:

Essential Questions

- What factors can cause people to leave their homes and move to a new and different place?

- What hopes and expectations do immigrants carry with them upon arrival in a new place?

Enduring Understandings

- Immigrants and migrants moved to Chicago and other American cities, pushed by economic and social strife, and pulled by hopes and expectations of freedom and economic opportunity.

- Immigrants and migrants came to Chicago and other American cities from many different places. They had some common motivations and expectations and some that were unique.

Objectives

- Students will read closely to determine what a text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it.

- Students will cite specific textual evidence when writing to support conclusions drawn from a text.

- Students will analyze how two or more texts address similar themes and topics in order to build knowledge.

- Students will write narratives to develop imagined experiences and events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences.

- Students will present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

Key Vocabulary

- anti-Semitism

- Chicago Defender

- expectation

- Great Migration

- immigrant

- Jim Crow laws

- lynching

- Mexican Revolution

- migrant

- motivation

- the Pale of Settlement

- pogrom

- racial etiquette

- sharecropper/tenant farmer

- Zapata/Zapatista

Standards Connections

Common Core State Standards

Anchor Standards in Reading: http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/R/

- CCSS-ELA Reading Anchor Standard 1: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1

- CCSS-ELA Reading Anchor Standard 9: ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.9

Anchor Standards in Writing: http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/W/

- CCSS-ELA Writing Anchor Standard 3: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.3

Anchor Standards in Speaking and Listening: http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/SL/

- CCSS-ELA Speaking and Listening Anchor Standard 4: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.4

Materials

In the Classroom

- chart paper and markers

- writing journals or paper

- self-stick notes in two colors

- a computer with Internet access

- an interactive whiteboard or another classroom projector

Works of Art

- Elizabeth Catlett, And a Special Fear for My Loved Ones

- Bernece Berkman, Jews Fleeing War

- José Clemente Orozco, Zapata

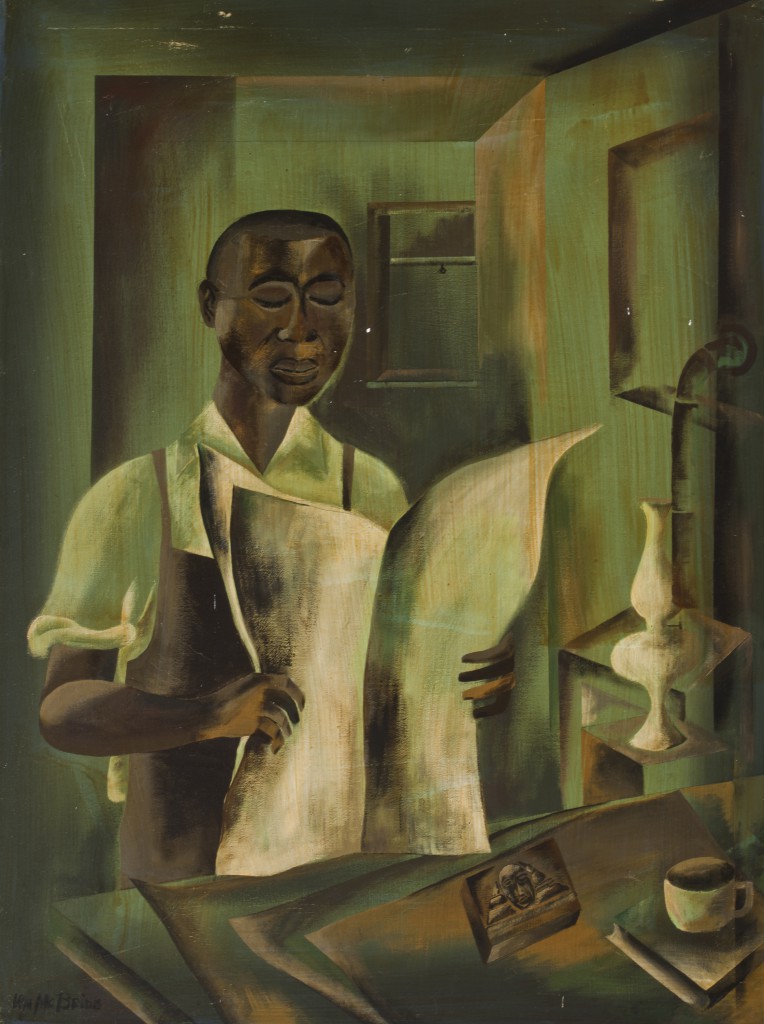

- William McBride, Robert Abbott Founds the Chicago Defender

Other Resources

- Art Study: And a Special Fear for My Loved Ones, Read to Build Knowledge

- Art Study: Jews Fleeing War, Read to Build Knowledge

- Art Study: Zapata, Read to Build Knowledge

- Art Study: Robert Abbott Founds the Chicago Defender, Read to Build Knowledge

- Push and Pull Factors, Document Sets 1-3

- Push and Pull Factors Graphic Organizer

- Venn Diagram of Push and Pull Factors

Lesson Steps

- Lead a “What would you take?” activity: Tell students to imagine that they must leave their home, possibly forever, and they can only bring what will fit into a backpack. Ask the questions below to help prompt the students. You may wish to make this a homework assignment prior to beginning the lesson:

- What would you want to take? What would you need to take?

- What might you have to leave behind that would be difficult?

- How would you feel as you made these decisions?

- Write down a list of the items you would bring with you. Be prepared to discuss why you would bring them.

- Have students briefly study three works of art: Project these images or provide copies of them to students:

- Elizabeth Catlett: And a Special Fear for my Loved Ones

- Bernece Berkman, Jews Fleeing War

- José Clemente Orozco, Zapata

Please note that the first image, And a Special Fear for my Loved Ones, directly reveals the violence of a lynching. The other two images suggest violence without portraying it as directly. Be sure to inform students that all three images were created by artists who came from the racial and ethnic groups that experienced this violence. The artists were expressing what they knew to be true. While it is difficult to view these artworks, it is also a way to honor those who suffered and endured during these terrible events.

Tell students to study each image for a few minutes to see if they can identify what’s going on in the image. Have them record their initial responses, using vivid words to describe what they see. To provide more guidance, pose questions such as the following as students are studying the images:

- What is happening in the image? How do you know?

- Where do you think this scene is taking place? What kind of place is shown in the image? What clues make you say that?

- In what time period might the scene in the image take place? What do you see that makes you think that?

- What do you notice about the people in this image?

- What motive might the artist have for showing this scene?

- Have students share their observations: Pair students and have them discuss their ideas about each image with their partners. Then have the class discuss how each image represents part of a violent series of events in the twentieth century that forced many to flee their homelands.

- Have students become “experts” on an image: Depending on the size of your class, divide students into three or six groups and assign an image to each group. Distribute copies of the related “Read to Build Knowledge” Art Study text to each student in the group—for either And a Special Fear for My Loved Ones , Jews Fleeing War, or Zapata. Members of each group should read the text together and note the additional insights they gain from the text about the image and the difficult situation it portrays. Then have representatives from each group present what they have learned about the image and how it portrays a situation that might make people decide to leave their homeland.

- Revisit the “What would you take?” activity: Ask questions like the following:

- Put yourself in one of the situations represented in the images. What factors would motivate you to leave?

- Imagine that you were fleeing from the situation depicted in the image. How would you change the packing list that you prepared earlier?

- What problems and dangers do you think you would face as you were fleeing?

- What thoughts and feelings would go through your mind as you prepared to leave?

- Introduce William McBride’s painting Robert Abbott Founds the Chicago Defender: Project the image and give students a minute to study it. Then discuss the image with questions like the following:

- What are the first things you notice about this painting?

- How would you describe the setting?

- What do you notice about the man’s appearance?

- The title of this painting is Robert Abbott Founds the Chicago Defender. What further insights does this give you about the painting?

- Share an informational text about the painting: Distribute copies of the Art Study: Robert Abbott Founds the Chicago Defender, Read to Build Knowledge. Have students work with partners to closely read this text and to find more information about the painting. Then discuss the painting and the text with questions like these:

- What does the painting show about the early days of this newspaper?

- In the painting, consider the expression on Robert Abbott’s face. After reading the text, what do you imagine he might be thinking at this moment?

- Based on what you’ve learned from this Art Study and the Art Study: And a Special Fear for My Loved Ones, what do you think the Chicago Defender meant to African Americans?

- Discuss push and pull factors related to migration and immigration: Explain to students that although the Chicago Defender was published in Chicago, it quickly became a national newspaper as African American train workers, mostly porters on Pullman Sleeping Cars, smuggled it into the South. The Pullman Company was once the largest employer of African American men in the age before most people traveled by car or airplane. Thanks to the many train workers who brought copies of the Chicago Defender to the South, the paper was influential in encouraging black people to leave the South and migrate north to Chicago.

Remind students that they have already examined the motivations that people have had for leaving their homelands, such as racism in the South, times of war in Mexico, and religious persecution in Eastern Europe. Explain that these motivations can be called “push factors” because they push people from their homes. When people go to a new place, they have expectations about how life in their new home will be better. These expectations can be called “pull factors” because they pull people toward the new place.

Ask students to consider why Robert Abbott might have wanted African Americans to move to Chicago. If needed, point out that the newspaper was important in publicizing the brutality of racism and violence black people faced in the South, and it publicized the opportunities Chicago provided, especially jobs. The Chicago Defender provided an ongoing commentary highlighting the push and pull factors around migration to the North.

- Introduce the document sets: Explain that students will work in small groups, and each group will examine one set of primary source documents. They will look for evidence in the documents that helps them identify push and pull factors for people moving to Chicago and other U.S. cities from the American South, Eastern Europe, or Mexico. Then they will share their findings with the rest of the class.

As background, provide more context for African American migration and immigration from Eastern Europe and Mexico in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

- African-American migration: Beginning with a slow trickle of migrants in the early 1900s, African Americans moved to the North in much larger numbers when defense factories needed workers during World War I. The opportunity to escape the prejudice, discrimination, racial violence, and poverty of the South was welcomed by many African Americans. Large northern industrial cities, like Chicago, were the destination.

- Immigration of European Jews: In the 1800s and early 1900s, large numbers of Jewish immigrants left Eastern Europe and moved to U.S. cities such as Boston and Chicago. They were escaping violent anti-Semitism, or discrimination against Jewish people. In the Russian Empire, for example, Russian rulers had confined Jews to a geographic area known as the Pale of Settlement, and they were not allowed to move freely throughout the empire. From the 1800s through the early 1920s, Jews were the victims of large, organized, brutally violent riots known as pogroms, which resulted in the murder of many Jews and the displacement of millions.

- Mexican immigration: The border between the U.S. and Mexico has shifted over time and movement was often fluid in both directions. Political instability, revolution, and poor economic conditions in the late 1800s and early 1900s caused many Mexicans to move to the U.S. While work in agriculture was common, many Mexican immigrants moved to Chicago and other cities when offered better paid jobs in factories.

- Have students analyze primary sources: Depending on the size of your class, form three or six groups of students. Distribute one document set from Push and Pull Factors, Document Sets 1-3 to each group, with each member receiving a copy. Note that some documents must be accessed online for permissions reasons. The document sets are:

- Document Set 1: The Great Migration

- Document Set 2: Mexican Immigrants in Chicago

- Document Set 3: European Jews in Chicago

Distribute copies of the Push and Pull Factors Graphic Organizer. If the groups designate a student to record their notes, each group will need one graphic organizer per primary source document. Alternately, each student can complete a graphic organizer for each document in the set. Tell students they should work together to analyze the primary sources in their document set. They should record the push and pull factors that led people to Chicago and other U.S. cities, citing evidence from the documents to support their identification and analysis.

If students need more support, you could begin by conducting a close reading of one of the sources for the class, modeling how to identify and record the push and pull factors. You can also ensure that the groups include students at various ability levels. Allow more time for students to examine and discuss each document. Circulate among the groups providing additional modeling and support as needed.

Point out that some of the sources have offensive language and/or describe acts of violence. Remind students that analyzing these sources will give them a deeper sense of the difficulties that forced people to leave their homelands.

- Have the groups present their findings: Distribute chart paper and markers to the groups. After each group has analyzed one of the document sets, the group members should prepare a visual on the chart paper that shows the push factors and pull factors that they discovered in their analysis. They should use the visual in an “expert” oral presentation that explains these factors to the rest of the class and presents evidence from the texts that supports their ideas.

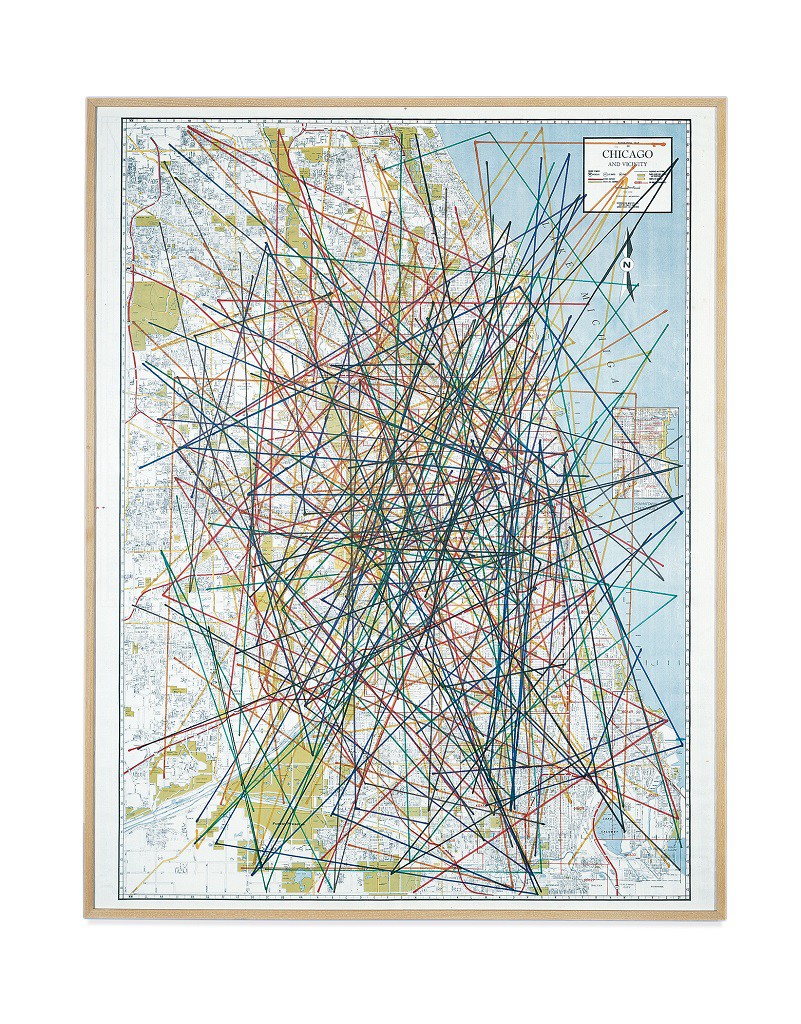

- Have students compare push and pull factors with a Venn diagram: Tell students that after hearing their classmates’ responses and after looking at the documents and artworks over the past days, they should be getting the sense that people moved to Chicago from Eastern Europe, Mexico, and the American South for many of the same reasons. Yet people also had unique reasons for moving. Explain that students will now work in groups to compare the motivations and expectations of people moving to Chicago in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Form groups of students that include “experts” for each document set. Distribute self-stick notes in two colors to each group. Have students identify the push and pull factors that led Jews from Eastern Europe, Mexicans, and African Americans to Chicago and other U.S. cities. Push factors should be recorded on one color of the notes, while pull factors should be recorded on another color. Students should record as many push and pull factors as they can for each group. On the self-stick note, they should identify and describe the factor and the group it applies to. On the board or on chart paper, create a large Venn diagram like the one shown on the Venn Diagram of Push and Pull Factors. Have students place the self-stick notes in the proper area of the diagram.

- Discuss the results: Have students examine the completed Venn diagram and discuss it with questions such as the following:

- Based on your work identifying the motivations and expectations of different groups of people moving to places like Chicago, would you say they have more common reasons or unique reasons for moving?

- Do any of the results in this comparison surprise you? Why?

- Think of other people who have come to live in Chicago from different parts of the world. Can you give examples of push and pull factors for them? In what ways are their motivations and expectations the same as the groups that you have studied? In what ways are they unique?

- Revisit the images: Divide students into small groups of three or four. Display the four images for this lesson again. Ask students to study the images again, and as a group, list three things they now know about what could be going on in each artwork. Have them list one or more questions they still have about the images. Then invite the groups to share their ideas.

- Have students write narratives about the images: Tell students to compose a narrative about one or more of the images that reveals the push and pull factors behind someone’s decision to leave his or her homeland. Students might choose to write a first-person narrative, a poem, a dialogue, or use another format to express the motivations and expectations of people who are migrating. They may work alone, with a partner, or in small groups of three or four depending on the format they choose. Invite students to share their narratives with the class.

Extension Activities

Write About a Move: Ask students to write a description of a move that they or someone in their family had to make. What were the push and pull factors that influenced this move? Alternately, students can write about where they would like to move and why, mentioning the push and pull factors that would influence their decision to go somewhere else.

Additional Resources

Challos, Courtney. “William McBride, Artist, Collector, Force For WPA.” Chicago Tribune, August 17, 2000. Accessed October 23, 2014. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2000-08-17/news/0008170106_1_collecting-art-institute-south-side

Grossman, James R. Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Herzog, Melanie Anne. Elizabeth Catlett: In the Image of the People. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2005.

Hughes, Langston. Langston Hughes and the Chicago Defender: Essays on Race, Politics, and Culture, 1942-62. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Lee, Jennifer. “The Last Pullman Porters are Sought for a Tribute.” New York Times. April 3, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/04/us/04porters.html?_r=0

Oehler, Sarah Kelly. They Seek a City: Chicago and the Art of Migration, 1910–1950. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2013.

Ottley, Roi. The Lonely Warrior: The Life and Times of Robert S. Abbott. Chicago: H. Regnery Co., 1955.

Public Broadcasting Service. American Masters Series. “Orozco: Man of Fire.” Accessed October 23, 2014. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/episodes/jose-clemente-orozco/orozco-man-of-fire/82/

Public Broadcasting Service. “The Black Press: Soldiers without Swords.” Accessed October 23, 2014. http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/index.html

Weininger, Susan. “Bernece Berkman.” In Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: The Pursuit of the New, edited by Elizabeth Kennedy, 91. Chicago: Terra Museum and University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Weininger, Susan. “Bernece Berkman.” http://www.chicagomodern.org/artists/bernece_berkman/